Notes on Labour Repression

A Tentative Tread into Labour Economics

Source: Pseudoerasmus, Labour repression & the Indo-Japanese divergence

(Note: With a spicy title like that, I feel obliged to mention that I don't know much about labour economics. These are just my thoughts on an interesting blog post I read. It starts with a plain description of the blog post, comparing it with another blog post I like, then rapidly descends into wild speculation. You have been warned.)

The Unresolved Contradiction

I've always been very ambivalent about unions. On the one hand, my impression is that unions have bargained for very nice things - 5 day work weeks, 8 hour work days, worker safety - which I very much enjoy. On the other hand, I also have the impression that unions have bargained for very ridiculous things, like unsustainable pensions, inability to fire incompetent people, and massive subsidies for unproductive industries.

An "enlightened" perspective might be that some unions are good, and others bad, depending on the particular leadership of particular unions. I'm thinking here of a hypothetical German union who supports mechanisation, retrains workers for different jobs, or exercises "wage restraint", but which otherwise strongly defends shorter working hours, tight firing rules, etc.. But "it depends" is never a satisfactory answer to anything, and it's easy for workers to suspect that their union is working for The Man, and for firms to suspect the unionisers don't really care about wages increasing productivity (does it really...?) so much as wages increasing.

The true enlightened question is, depends on what?

Noah Smith wrote a convincing defense of unions in service industries in Why I love the new labor movement. The core of his argument is that unions have two failure modes:

When there are few or no real checks on union power i.e. the public sector union problem. Unsustainable teachers' union pensions in the US or massive subsidies for coal miners in the UK before Thatcher seem to fit this failure mode

When unions face un-unionisable foreign competition, and as a result put their employers' at long-term competitive disadvantage against foreign companies. The automotive industry in the US seems to fit this failure mode

Starbucks and Amazon warehouses, Noah Smith argues, are not subject to these failure modes. They are not essential public services. Resisting the introduction of new technologies in these competitive industries will ultimately lead to the loss of their own jobs, so unions are incentivised to increase productivity, no problems.

Pseudoerasmus' blog post on historical labour repression in India and Japans early industrialisation seems, on its face, to fit Noah Smith's thesis. In summary, Pseudoerasmus' post argues that, for various structural reasons, labour resistance to "labour intensification" in textile production was much stronger in India that in Japan, which resulted in the decline of Indian textile exports relative to Japanese. As late as 1913, Britain accounted for 75% of global cotton textile exports, with Indian domestic production catching up to British imports and catching up to British exports in China. By 1937, Japan accounted for 37% of global exports, Britain 27%, and India only 3%.

As for the structural reasons, Pseudoerasmus offers three main points: First, the differences in agricultural productivity resulting in different levels of surplus labour. Japan followed the Lewis model of surplus agricultural labour driving industrial development ("You could just beat the fields with a stick and the peasants keep leaping out."); Second, the unwillingness of the British Raj to suppress Indian workers compared to the Japanese government (Pseudoerasmus riffs off Marx with the brilliant quote "The British Raj was not a committee for managing the common affairs of the Indian bourgeoisie"; Third, is differences in the characteristics of the labour forces of the two countries.

The third point, differences in the characteristics of the labour forces is what Pseudoerasmus' spends the most on, and is the most interesting:

Indian mill workers were around 80% male, while Japanese mill workers were around 80% unmarried females

"Regular" Indian workers were strongly attached to their jobs, and by 1940, more than 50% had a tenure longer than 10 years. Whereas Japanese country girls (at least in the early years of industrialisation) expected to get married and return to countryside. They had little incentive to suffer the costs of strikes while receiving little of the benefit. By 1936, only 8% of workers had a tenure longer than 10 years. But returns to experience in textile produced decreased after a few years. Japanese mills obtained "optimal" turnover: High turnover reduced labour power in a specific firm, while increasing the industry experience of the overall labour force over time

India, being prone to monsoon, developed an unusually strong co-operative culture. Workers struck to maintain the employment of their village networks, and could depend on their village's support during long strikes. In Japan, girls were recruited far from their eventual work sites (as far as Okinawa to Osaka), with their families signing their labour contracts. The girls lived in company dormitories, and if they ran home, the families often supported the company

Indian workers were recruited through "jobbers", foremen who recruited from their patronage networks drawn from caste, kinship, village, or neighbourhood ties; This fragmented the labour market, and since day workers were also recruited through "jobbers", Indian mills could not recruit day workers as scabs to break their power

Pseudoerasmus draws a difference between "speed-up" growth where machines get faster, and "stretch-out" growth/"labour intensification", where each worker handles more machines. In 1910, Indian and Japanese textile mills had similar levels of "labour intensity", at 200 ring spindles or 2 looms per worker. By the early 1930s, Japan tripled its labour productivity to 600 spindles or 6 power looms per worker, while India's ratio remained the same. Overall labour productivity in spinning in India grew only 20-50% between 1890 and 1938. In Japan grew 400%.

Now, Pseudoerasmus is clever enough to not to state it explicitly, but what he describes implicitly is a clear argument in favour of labour repression as a matter of state policy. Again, this fits Noah Smith's thesis, specifically the "un-unionisable foreign competition" failure mode. But there is a deeper contradiction between the two posts. (Noah Smith is also aware of this unresolved contradiction, I think, since he was the one who pointed to Pseudoerasmus' blog post in a different blog post I cannot remember the name of...)

The contradiction is, labour power is what made jobs good. Per Noah Smith:

unions were a big part of what made manufacturing jobs good. Factory jobs were low-paid and involved horrific conditions in the early Industrial Age; only once unions took over did factory work transform into the dignified, well-paid sort of job that we now associate with the mid-20th-century middle class.

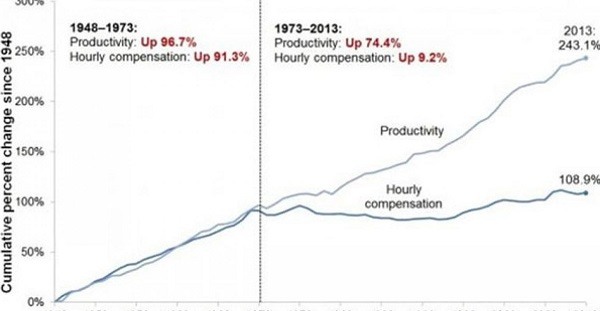

Without labour power, we might get something like this:

Which is our classic graph showing the decoupling of productivity and wage growth. There are problems with this graph, but Scott Alexander argues convincingly (to my untrained eye at least) that while the decoupling is less severe than it looks, it's still a bad thing which exists. (Scott also argues that de-unionisation is not a big part of the decoupling but I'm just going to take Noah's word as an actual economist over Scott's.)

But labour power also "eats" all the gains of productivity growth, resulting in capital underinvestment, so labour is not "freed", so labour's bargaining power remains too strong, so labour "eats" all the gains of productivity growth, resulting in capital underinvestment...

In India, textile mills experienced 8 general strikes in Mumbai alone between 1918 and 1938. The 1928 and 1929 general strikes - against the "rationalisation" of textile production by reducing workforce and increasing workload in exchange for increased pay - effectively stopped textile production in Mumbai for those years.

Since Indian textile workers refused to increase their workload, machinery like the automatic loom, which could be used 20 per worker by Japanese mills, could only be used 4 per worker by the Indian mills, not justifying the costs of the machine. Nor could Indian mills pay for increased productivity, since labour costs increased in lockstep with increased productivity, so that productivity-adjusted wage levels remained roughly the same across the country. The few Indian firms which did "rationalise" did not see increased profits, so really, why bother? Far easier to have the British Raj impose tariffs on foreign textiles. Trade protectionism is the devil's bargain between labour and capital.

///

The Least Convenient Possible World

If I were someone who believed reality was convenient, I might argue that unions were not necessary to raise living standards, resolving the contradiction. That, for example, software engineers don't have unions, and yet are paid extraordinarily well. That, in the final instance, wage is determined by labour demand and supply, and everything else is distortion of the market's price mechanism.

I am not such a person.

It seems obvious to me that the surplus of co-operation does not have a "natural" or "moral" distribution. I can't find the source (curse you, Reddit search!) but I remember clearly a photo of a man taking a photo of himself with a widget that he "made", comparing the however many dollars per hour he made to the hundreds (thousands?) or so the widget would sell for, denouncing "capitalism". Even Reddit's very left-skewed commenters skewered him. Who made the machine he operated to "make" the widget, the machine the widget he "made" would be used in, the ideas and systems behind those machines? Everyone thinks they deserve the full profit of the final work as if was their holy touch that sanctified it; From the factory worker who made the object, to the salesman who sold that object, to the new-minted capitalist who scrimped and saved to buy the factory. (Though, why should his prudence even matter in this moral calculation? Was he not already paid for his initial labours, and should therefore benefit no more than a prisoner should suffer upon becoming a free man?)

"You" are indispensable, but so is everyone else.

Thus the distribution of surplus can only gravitate towards two poles: Bargaining power, and pragmatic calculations. A pragmatic union would withhold from the full use of its power to avoid damaging its host, but whether a worker takes 10% or 90% of the surplus he created in co-operation with his fellows is ultimately a matter of how much his fellows need him, and how successfully he manages to convince them he deserves what he asks for.

To shift bargaining power from a world 10% in favour of the workers to a world 90% in favour because (hypothetically) a popular new movie celebrating Marxist thought was released and now everybody tacitly agrees to co-operate against their employers cannot, in my view, be called market distortion. What makes unions different?

And if we were to make a reference to the creative destruction of firms who mistreat their customers or workers, could we not (excluding the failure modes discussed above) also apply that standard to the unions? Or is one additional layer of abstraction somehow a step too far?

I would agree with Noah Smith on modern libertarians' defense of "free markets": It is often a defense of "local bullies" (work bosses, neighbourhood associations, organised ethnic/religious groups, etc.) against the "big bully" of the government, a "don't tattle to the teacher ideology" that hinders the freedom of the average person. A "free society" which allows a boss to prevent the free association of his workers to discuss their mistreatment does not seem to me very free.

At the same time, it is easy to imagine a union boss oppressing his cohort, favouring his own family and friends, demanding bribes for jobs in much the same way that local foremen with their patronage networks did in early industrialisation everywhere. On Reddit at least, it seems common knowledge that labour organisations withhold welfare unless recipients vote or protest for them.

I do not need to speak of the tyranny of Stalinist Russia or Maoist China.

Everywhere the "average man" turns, there stands the shadowy figure of a "bully" far greater than he. Perhaps that is sufficient evidence the entire framework should be thrown out head and foot; If all someone sees are lurking shadows, that's paranoia, not prescience. A smarter libertarian might argue: Yes, bullies of any kind are bad. Yes, governments can do great good. But the worst kinds of governments produce bad outcomes incomparable to any local bully, therefore we should hinder it regardless of potential benefit. This is an ideological position, and in any other context the libertarian would argue the exact opposite. That technology regardless of its past harms - and potential for incalculable future harm - is nevertheless capable of even greater good and should therefore not be hindered. If so for nuclear power, or AI, or any other "shiny" technology, why not for the technology we call "government"?

If it is great to be daring, why not dare to be a great politician?

///

A Digression on Discretion

The problem at the heart of popular "debates", I think, is the assumption that things exist, or can ever exist, in platonic states. That there exists a platonic "government" and a platonic "corporation" which behave consistently in response to consistent incentives, whether it be platonic "power" or platonic "profit". Thus a platonic "observer" - in whose seat we place ourselves - can imagine an ideal system to strive towards, even if we concede that this ideal can never be achieved.

The belief in this ideal, though possibly useful for political co-ordination, is fundamentally irrational. If there exists one hundred different variations of governments, workers, unions, corporations, etc., due to differences in initial conditions, external influences, local cultural evolution, and so on, which all respond differently to the same (differently propagated) "push", any sort of reasoning based on platonic forms rapidly becomes delusional. A silly demonstration of this is this blind and deaf run of Pokemon Fire Red, where the player receives no feedback to their inputs, and has to engage in all kinds of silliness to guarantee all possible random states of the game sync up. Silliness aside, all complex systems can be described as follows: Systems can be feedforward, sending signals to the system while making assumptions about the internal state of the system and its external state of the world to reach an assumed state; Or they can be feedback, waiting for signals from the system before calibrating the system with new signals.

Feedforward systems can be very powerful. My sense is the vast majority of efficiency tricks in software engineering rely on making strong assumptions to avoid performing unnecessary operations. I think it works for any major investment by governments, corporations, or even individuals where the payoff is more-or-less known e.g. building public transport systems, expanding production capacity, college education (if only for signalling). If we already know with high certainty that something is the right thing to do, waiting for feedback we already expect is suboptimal. But when uncertainty is high, which is be definition the case when we want to implement policy innovation, it seems obvious to me we cannot rely on feedforward.

Instead there must exist a wide range of ideal intermediate system states, defined vaguely as a group of states which seem better than the next group. We are only able to navigate between these fuzzily defined intermediate states with a lot of guesswork and constant corrections based on short-run feedback. I specify intermediate system states because, obviously, the true end state is fully automated luxury space communism /hj.

Even figuring out the what intermediate states are better is hard. Part of the reason I wanted to read Pseudoerasmus' blog post is because I wanted to fill my head with the nitty gritty details that are necessary to reason about the development of specific industries or the effectiveness of specific labour arrangements. And while it's "entertaining", noting down the interesting bits I read and thinking over them is on track to take me the better part of a few days. Days which I could be using instead to do normal people things, if I knew what they were.

It's easier to handwave the hard parts with "It's not possible to know everything 🤷♀️," while still acting like one knows everything. "We must make simplify complex problems to even begin to solve them" is something I fully agree with. Yet, when I simplify a software requirement to start with, then forget I haven't solved the actual requirement when submitting my solution, I have the decency to feel embarrassed. Why even attempt to generalise about "governments" or "corporations" a whole, across the whole span of time and space? In engineering, optimisation comes from not solving problems we do not actually have: "Anyone can design a bridge that can stand, but it takes an engineer to design one that barely stands." How much do generalisations about "governments" really inform my understand my own government, compared to how much effort it takes to understand the world?

I think everyone who's a little educated about politics is aware that most people who are talking about politics are talking out of their arse. The trap is that most people who are very educated about politics, including me, are talking out of our arse. The only way to understand a complicated system is to be in the system. To interact with this particular union leader or that particular business group. To exercise discretion, and reap the rewards of good judgement. To act upon the system as a particular actor, not a disembodied, unfeeling platonic "observer".

I... am not quite there.

///

Primal Fears

I think it's important to emphasise that productivity growth is a "vicious cycle", in both senses of the term. Not knowing anything about British economic history, I found the description of rising agricultural productivity in pre-Industrial Britain (~1700s) in Peter Mathias' First Industrial Nation convincing. In summary, inheritance law changes allowed landowners to more easily borrow against their land, leading to landowners borrowing more to buy more land, leading to capital investments to increase agricultural productivity to pay off the interest on those loans, leading to smaller landowners becoming unable to compete, leading to... Which was vicious towards small landowners, consolidated land under a few larger owners, but which also released agricultural labour for the Industrial Revolution, and ended famines in England. Compare England to France, where no such consolidation happened, and where famine eventually led to the French Revolution.

Capital accumulation, so hated by those who are "anti-Capitalist" (however the term is defined), was critical to the Industrial Revolution and the staggering productivity growth it enabled. Even if capital accumulation is not always critical, the fact that it sometimes is should give us pause. Pseudoerasmus gives a reasonable rule of thumb:

More equal distribution of income can promote growth when returns to skill are high;

More inequality promotes development through profit-driven capital accumulation when capital is scarce, and returns to skill are low

Japan's economic convergence with Western countries was accelerated by capital accumulation at the expense of real wage growth. (Though Pseudoerasmus notes correctly that holding down real wage growth does not imply wage stagnation, just that labour productivity growth > real wage growth.)

Curiously, this rule of thumb would imply that in our current age of capital sloshing around with nowhere to go, where we as a society need much more investment in hard skills, the optimal state policy might be to suppress capital. I'll return to this point later. What I want to focus on for now is, given the inconvenient reality that accumulation of capital is sometimes necessary:

How do we deal with this icky feeling of unfairness, where the accumulation of resources by others leaves us increasingly behind for no reason other than our initial conditions?;

How do we manage phase transitions between needing more capital and needing more labour?

Taking an inconvenient point of view, I think the ickiness... Cannot truly be exorcised. The moral arguments for the accumulation of capital tend to follow two branches: First, that it is deserved for the exercise of moral virtue; Second, that is utilitarian, since profit is necessarily driven by increased consumer utility. I am sympathetic to the latter, not the former. From a societal perspective, thrift and industry are pro-social virtues which should be rewarded, but so is charity, which seems rather less promoted by those who expound their individualistic virtues. Nor does a moral virtue imply a munificent reward as opposed to customary one, nor is it obvious to me that being born more inclined to achievement or to a family with greater ability and inclination to nurture is necessarily "virtuous".

As to the latter, Peter Mathias had a lovely few paragraphs:

The elemental truth must be stressed that the characteristic of any country before its industrial revolution and modernisation is poverty. Life on the margin of subsistence is an inevitable condition for the masses of any nation.

The population as a whole, whether of medieval or seventeenth-century England, or nineteenth-century India, lives close to the tyranny of nature under the threat of harvest failure or disease.

The graphs which show high real wages and good purchasing power in some periods tend to reflect conditions in the aftermath of plague and endemic disease, as in the fifteenth century. If one looks to the late-fourteenth- and fifteenth-century England as the golden age of labour as Thorold Rogers did, it is really the equivalent of advocating the solution of India's difficulties now by famine and disease - of counting it a success to raise per capita national income by lessening the number of people rather than by expanding the economy.

This is an argument made by many economists, and I think a true and important one. This is also an argument not well understood by those outside of economics. It feels like one of those maths proofs where you can follow all of the steps, yet the conclusion leaves you scratching your head. Who, after all, truly believes anyone can create bread from air? This disbelief manifests in many forms, notably in arguments for "degrowth", but also shows up in arguments for reparations, as if the wealth accumulated by United Kingdom could be fully accounted for by the exploitation of her colonies, as opposed to the wealth of South Korea, which apparently sprung from nothing.

This argument cannot be understated, yet it cannot exorcise the ickiness of capital accumulation. We rationally fear snakes and spiders and a rustling in the underbrush, even though most snakes and most spiders and most rustling bushes are harmless to us. The present goodness of a particular capitalist does not convincingly tell us of his future goodness, the goodness of heirs, or the goodness of other capitalists superficially similar to him.

While I think the case that money is power is very overstated; That billionaires can't somehow pull the strings of politicians like hackneyed political cartoons; That if that was true Jeff Bezos would not allow himself to be endlessly harangued by progressive Americans any more than Vladimir Putin would; I also think it would be absurd to claim unequal distribution of resources ("legitimately" earned or not) did not matter in the social calculus. Even if I trust Mr. Generous and Wise not to abuse his position on the school board - acquired because of his $1 million dollar donation to expansion of the school library - all else being equal, I would rather not have to trust him at all. The fact that Mr. Generous and Wise has performed a utilitarian virtue by providing a service consumers wanted for money; The fact that he has then provided a second benefit by donating a portion of his profits; These facts are no more absolving of my worries than the carefree student who claims I do not need to worry about studying, since, historically, most students pass their exams.

I also would not go as far as to argue that one should complain and litigate endlessly under the guise of "continuous improvement" like a know-nothing manager whose only resort is toothless authority. A good judge knows well the law and enforces it strictly, yet she does not stand on the sidewalk haranguing passers-by, warning them against committing crimes, dragging some of them to court because they "looked suspicious". Publicly accusing someone for violating a moral norm when they have not is as obnoxious to and discouraging for Mr Generous and Wise as it is for Mr Powerless and Disenfranchised. From my point of view as an "engaged citizen", I want to encourage good behaviour where it occurs and discourage bad, however limited my viewpoint, because that is all I can do. Not stand as a disembodied "observer", marking down everyone against a platonic ideal of "good".

(Who am I, to state so strongly my belief in "society" and "co-operation" and "discretion"? Fat load of good being a collaborator will do me when it's "my time"! So hissed the feral kitten, its arched back pressed against the wall, as it clawed at the giant hand which approached it. My government has always treated me well, as have the people around me. It would be idiotic as well as immoral to forgo the benefits of co-operation out of fear of defection, when the other side is already co-operating. As to the vague accusation that being sincere is somehow embarrassing, Contrapoints made one of my favourite quotes ever when she was trying to persuade her lefty audience to vote for Biden against Trump: "Isn't being involved in politics inherently not cool? Because politics is for people who believe in things. People who place their hope in fallible human beings. All of which is very not ~cool~")

To complain indiscriminately is bad, but to handwave away the movements of the system as "self-correcting" is also terrible. What is the "correct state" of a ball floating on a point in the middle of the ocean? A single wave pushes the ball then pulls it back to its original position, but if a second wave pushes the ball in a different direction in between, then a third, where does the first wave pull the ball back to? Everything is moving all the time. It seems self-evident that fast changes can destabilise slow corrections. Random noise can cause destructive resonance. Evolution drifts towards higher utility, but acute shocks can "trap" creatures in bad niches when the shock fades, and there's no guarantee any local optimum is as good as neighbouring optimums. Purposeful actors can easily break rules-based system which assume actors will act in a certain way.

Libertarians long for a "perpetual balance machine", which maintains its own equilibrium without "external influence". But a bicycle can never balance itself, because "we" are its balancing mechanism. Just as the student will pass his exam, so long as he studies, any political and economic system will only work if "we" are jammed between the gears: Cutting expenditures when costs rise, retraining when our industry is in decline, defending moral norms against labour exploitation, voting against parasitic unions, and so on. Jammed between the gears is an unpleasant place to be, but this feeling of unpleasantness is as necessary to the political-economic system as the feeling of pain is to the body.

What about the argument that wealth does not persist across generations in any case - "shirtsleeves to shirtsleeves in three generations" - so there is nothing to be overly concerned about? I should look up the data, but my impression is that wealth transmission is at least stagnant or even increasing. There is at least one credible-seeming academic book about the persistence of wealth across generations, and I vaguely recall a convincing argument that social immobility in the US is disguised by the children of wealthy families often to choose high-status low-pay work in, for example, NGOs. The latter strikes me as intuitively true. Human capital does not accumulate only in the form of wealth, and the debt-burdened literature student is still wealthier than the work-a-day homeless man who has strictly higher net-worth. As long as wealth transmission is not somehow decreasing, the point I want to make will stand: I very much appreciate the stupidity and empty vanity of the rich, which allow the the more clever and frugal among us to catch up; To make an argument based on the continued stupidity of the rich has no grounding in reality. The rich learn as well as the poor, and wealthy parents may well learn to store their wealth in trust funds, or simply get better at passing on their knowledge as well as their wealth through cultural evolution.

There is a more careful argument that wealth accumulation is naturally limited, which I favour if only because I'm an unremittingly arrogant young person and fundamentally believe I can achieve whatever I please: Wealth, as well other more slippery resources like knowledge, face diminishing returns. This limit is not universal (who knows what the real limit to anything is), but rather a limit of "coincidence". Wealth needs the right ideas and the right circumstances to transform into profit. Absent the other two, wealth does nothing on its. So the wealth of one person is forced to idle, while the lesser wealth of another - facing different circumstances - is allowed to catch up. This is also true, I think, for knowledge. Netflix's The Mole has a contrived but amusing and perhaps true-to-life example: Two teams were competing to solve a sequence of puzzles to obtain a code, which would allow their team to avoid an elimination vote. The first team quickly solved all but the last puzzle, which was frustrating obscure. Eventually the second team arrived at the last puzzle, and also got stuck. The producers gave a hint to the final puzzle, and it was a close race to the finish. In other words, nothing mattered but the final puzzle. It is not for nothing Paul Graham wrote in his advice on How to Do Great Work is to get to one of the frontiers of knowledge; Everyone is waiting there.

But.

Though I personally believe it, and it seems to be true enough for the technological changes I have personally experienced, diminishing returns is ultimately an argument on faith. There may well be an idea out in the great unknown where wealth alone, unconstrained by anything else, is sufficient to have asymptote at infinity. Will I accept the libertarian bargain that, as long as my life is slightly better - perhaps I can easily afford a VR headset now, instead of balking at the ridiculous cost - I should be happy there is a trillionaire having grand space adventures and establishing a vast space empire in Alpha Centauri? Is it all good as long as I dutifully enforce moral norms against the ill-treatment of Martian miners? No, of course not. Just the thought of someone having fun I want to have but can't have pisses me off.

Thus we have finally fallen flailing down the cramped shaft of this whole moral apparatus we have built, and arrived at its cavernous base. The truth is, I am accepting of the status quo because I, personally, am happy with the status quo. The rich can have their yachts and Rolex watches; It makes no difference to me whether I'm browsing LibGen in my room, or in a cottage overlooking the Senne. I may want things I do not yet have, but I do not feel constrained in getting them, which I implicitly believe is just a matter of time. Someone else having (hypothetical) super fun space adventures I can't have though, though? That's a step too far for me.

I once read a claim that deontological ethics was incoherent, and could only be defined in contrast to consequentialism, without making claims about itself. That even the prohibition against murder is ill-defined. What, after all, is murder without the consequence of someone dying? Consequence is the bedrock upon which our moral apparatus is built; Ought must imply can. Any band of bohemians can claim that it is human right to live well and not work and form their own community. If they succeed, perhaps it is. If they fail and return to society with their tails between their legs, it cannot be. A religious government can claim it is moral to not eat certain foods, not wear certain dress, and not gather on certain days. If no one particularly minds, perhaps it is. If this immiserates the country and results in the government's overthrow, it cannot be.

Politics is the environment in which moral genes are tested; In Democracy faster than in Autocracy, but they are tested regardless. In this view, there are many "fit" moralities. Again, we reject platonic ideals. Again, we reject the disembodied "observer". Again, we must act as ourselves, propagating our own beliefs, constructing our own niches to fit ourselves, in so doing increasing our fitness for our environment. I very much like the status quo of many highly skilled migrants Singapore and think it benefits everyone, however much some dislike it. So I will defend it to those around me.

Finally, I return to the question of labour vs capital, which began this whole discussion. It seems to me that, due to diminishing returns and information lags, for any industry there would be periods where capital is scarce and labour is plentiful, and vice versa. Separately, there may be periods of high or low returns to capital or skill. In a naive, friction-less world, state policy encourage the distribution of profit to capital when returns to capital are high, and to labour when returns to skill are high. This will cycle back and forth depending on mysterious technological factors (we cannot predict if technological discover will slow down, only observe if it does), in much the same way the we now regulate interest rates. I suspect this obvious idea is already well-known among economists. I just have never heard of it, so it's still intriguing to me.

The problem with this "active equilibrium" idea is, of course, everything. Putting aside measurement issues, I somehow doubt a businessman who accumulated wealth rapidly when capital had high returns would volunteer to give up more of his income just as the return to capital fell and his income growth was slowing down. And why would a worker work for ten years for this businessman, trusting blindly that when the time came, he would reap a greater share of the reward? I used to find compelling the argument that economic growth should ultimately benefit "the people", and that growth without benefiting "the people" is pointless. On reflection, it's a half-silly argument, because I could just as well argue "Earning money is for the sake of enjoying it, why earn money if I don't spend it?" and then squander all my savings on some shiny thing. But it's only a half-silly argument because the person who saves and the person who benefits from saving can be two different people.