The Phase Diagram of Reality

On the Usefulness of Knowledge

(This was an essay I wrote in Chinese then translated back, so the sentence structure might be a bit awkward - If I rewrote it from scratch it might be a bit better, but then I would never bother to rewrite it from scratch so this is all you get :P Also, I know I haven’t been posting much, but I swear I’m up to a lot of stuff! I just haven’t gotten around to writing about it!)

What, exactly, is "intelligence"? What does it mean to be "intelligent"? Like many students who did well in school, my parents, teachers, and classmates called me "clever", and that name then became a part of my identity. If you believe a certain popular (wrong) school of thought, then the adults around me made a huge mistake: What we should praise in children is not their intelligence, but rather their hard work. After all, a child is either intelligent or they are not, and there is nothing hard work can ever do to change that. Therefore (according to this school of thought), children who are labelled as 'clever' inevitably become lazy, eventually falling behind in class when their natural talents are no longer enough on their own.

I think that's just dumb and wrong. It is exactly because I thought of myself as "clever" that, even when I was a dumb kid, I would pretentiously read world news on a big ol' newspaper spread on the floor, read hardcover books (in class, while ignoring the teacher, lol), listen to philosophy podcasts, etc. After all, if I really was an intelligent person, then I should be doing all the things intelligent people do. And if failed to do intelligent things, then obviously I was not intelligent.

And I wasn't going to just accept that, was I?

You might have noticed something backwards about what I just said: Logically, innate intelligence leads to outward intelligent behaviour. An idiot might pretend to be clever and do the things that clever people do, but that's all it will ever be; a pretense. Yet, a personality flaw I think a lot very clever people have is that they have this overwhelming desire to prove their own intelligence. And this kind of backwards logic shows up everywhere: the whole idea of predestination in Calvinism (and possibly the source of the moral belief that greedisgood for a large number of people) is that if you are one of God's chosen people, then even if the choice is already pre-determined, you can still prove that you were chosen by showing the signs of His favour i.e. becoming wealthy.

The point of this essay isn't to ramble on about what the nature of intelligence is, or what the best way to educate a child is; those are just examples of arguments in a topic that everyone is familiar with. Like, I can go on and on about how believing that I'm just so fucking clever, based on absolutely nothing at all, gave me the determination to bang my head over and over on the same problem over many years (I am just now FINALLY starting to understand electromagnetism.) But at the same time there will always be someone equally convinced that believing they were intelligent caused them to get lazy in college and eventually drop out, ruining their lives forever (though, to be fair, I did fall into this category for a bit before I figured out how to frame things in a useful way.)

Because everyone has different personalities, beliefs, and experiences, the exact same policy can have vastly different effects on different people. Even the same policy applied to the same person at different times and in different life circumstances can have vastly different effects! Two podcasters can argue about "the nature of intelligence" from noon to midnight and still come to no satisfying conclusion. These weighty so-called “topics of great import” have been debated by philosophers and the jabbering class for at least two thousand years at this point - as much of a blowhard as I am, I'm not so much of a blowhard as to believe I'm going to resolve these debates.

Not that I have any interest in resolving these debates. My whole point is this: whether an argument is completely accurate or not, whether it is completely logical or not, it doesn't matter at all!

The world is ridiculously huge and complicated. Like, forget about there not being simple answers. There may not even be answers at all! Since every effect has a thousand causes, and every cause likewise has a thousand effects, changing one thing for the better necessarily causes another thing to be changed for the worse (though the sums of better and worse may lean one way or another.) Because the world is complicated, and because human knowledge is so imperfect, every argument necessarily has some loose thread you can pick at to unravel the argument. Therefore, we cannot rely on the existence of a flaw in a policy or argument to determine whether the policy or argument is good or bad!

I want to rant about the imperfection of human knowledge for bit, because it’s one of my hobby horses, and this is my blog post. Obviously, because we don't have infinite time and attention, we can't fully investigate every question that comes our way. But the problem is deeper than that. First, because we can only observe something happening after it has already happened, every observation comes with a built-in time delay. To the soviet central planner or the CEO of a multinational conglomerate, it doesn't matter how accurate information is when it's transmitted from some faraway outpost of their domain; by the time the information travels to them it is and always will be already wrong.

Second, whenever we measure anything, we inevitably change the thing we measure. Like, I can mess up some guy's precision engineering project just by being an ass and walking around their lab in circles, radiating body heat. (I was tempted to refer to the Uncertainty Principle here, but apparently that's not caused by the act of measurement? I don't really understand.)

Third, because different methods of measurement produce different measurements even of the exact same thing, every measurement implicitly relies on a uniform system of measurements. To a peasant farmer deciding whether it's worth exchanging one "bushel" of rice for one "string" of coins, it matters whether the city market's system of measurements work with his village's system of measurements. A more mathy example of this point might be to point out that, if your rulers are small enough, coastlines can have infinite length. This is because ideal lines have infinitesimal width, and therefore we can fit an arbitrarily long line into an arbitrarily small area, breaking the intuitive correlation between length and area. So any comparison of two countries’ coastlines is kind of meaningless if the coastlines have not been measured by rulers of the same length.

And while it might seem like I'm arguing against the use of logic, I'm really not. One of my favourite quotes is by Isaac Asimov, and it goes something along the lines of: "When people thought the Earth was flat, they were wrong. When people thought the Earth was a sphere, they were wrong. But if you think that thinking that the Earth is flat is as wrong as thinking that the world is sphere - You're wronger than the two combined." And then he goes on to say that people who think like that suppose it is possible for Earth to be a sphere one day, a donut-shape the next, and a hypercube the day after that. Which is just an absolutely hilarious mental image. Sometimes problems just have correct answers, and thinking about these kinds of problems in a very forward-looking, premise-premise-conclusion sort of way is necessary!

And sometimes thinking in this sort of way is as dumb as a bag of rocks.

Imagine, for a moment, being back in school. You're at the base of your favourite stairwell. Then, let us analogise "making a logical deduction" to "climbing a flight of stairs". It is obvious to us that as long as we keep climbing we will reach the highest floor. Now suppose, on the other hand, we're climbing an Escher staircase. Equally as obviously, we can climb as hard as we want; we will never go anywhere. Clearly, simply following some step-by-step algorithm is not fully sufficient, and we must consider the interaction of the algorithm with the structure of the space we are applying the algorithm to.

(Regarding the interactions between unit-step and global behaviours - in retrospect the reason I struggled to understand physics in school was that I didn't understand the difference between the two. For example, we all know that light always travels at the speed of light. How then, can light "slow down" in order to explain refraction? The answer: when an individual photon of light hits glass, the atoms of the glass absorb the photon before releasing another photon a little while later. (EDIT: This is not correct, I misremembered 3Blue1Brown’s explanation. The photon does not get absorbed, since the photon is not at the resonant frequency of the electrons i.e. the frequency associated with the quantised energy required for the electron to jump an orbital. But I don’t fully understand what happens instead so I’ll just leave it there. Regardless, while no individual photon travels at anything other than the speed of light, the "ray of light" that we've mentally super-imposed onto the collection of photons occupying this space appears to slow down. Additionally, when a wave of light "bends" on hitting the angled glass of a prism, it is not because the individual rays of light are somehow changing their minds about where they want to go. But because all of the rays of light that make up the wave hit the angled glass at different times, and therefore the "wave of light" that we've mentally super-imposed onto this collection of light rays appears to bend. Much like how if you pushed a stack of coins in a straight line against the same angled glass, the coins naturally just kind of lean over.)

Of course, we're not disembodied consciousnesses observing our little three-dimensional world from the void of the fourth dimension. So whether we should compare a particular problem to a "school staircase" or an "Escher staircase" is not actually straightforward to determine. Since it is not possible to determine what is globally true, we are forced to rely on local approximations, and I would argue the best possible local approximation is to "go by results". From the point of view of "going by results", if I keep returning to the same floor, then I can reasonably infer that I am in a situation comparable to the Escher staircase. Whereas if I keep climbing and keep reaching new floors, then I can reasonably infer that I am in a situation comparable to the school staircase. (I don't fully understand the implications of it, but the size of the "look-back window" matters a lot here; if I'm on an Escher staircase and I only remember the last two steps, I will still never realise I'm in a loop.)

Let’s apply the principle of "going by results" to the topic of the ideal education system. Because, as we discussed earlier, the same policy can induce different outcomes in different people, we must necessarily first consider who our policy is targeted towards. Is he an excellent student, who is being carefully raised by diligent parents? Or is he someone who is falling behind? Is she someone who is excessively confident, to the point that when she is wrong, she says it's the teacher who made a mistake? (The last example might be from my personal experience :)). Or is she a student who doesn’t even dare to raise her hand? And this student who is falling behind, is he studying but somehow not understanding anything? Or is he not studying at all? And if she is not studying at all, is it because she thinks school is a waste of time, or is it because she's afraid that if she studies and still fails, that would prove that she's stupid and so she doesn't want to even try? Does he even need help? Maybe he plays video games every day but takes classes seriously enough to cram before exams, so he's perfectly fine, actually. Or does he have a certain image of himself e.g. as a delinquent, and doing well in school would mess with that? And so on and so forth.

That's just one student. If we were really serious about designing an education system, we would have to consider all of the students in the whole country. For the sake of simplicity, let us only consider secondary school students. In developed countries, 13- to 16-year-olds are about 4% to 6% of the total population. Using Singapore as an example, that's about 200,000 students. Which is to say, we would need to consider, for these 200,000 students, their personalities, beliefs, habits, parental background, etc.

Obviously, that's impossible. So, why do we still insist on playing at being our society's central planners? Conversely, if the student being considered was our niece or nephew, we would naturally (I hope) put in the effort to consider their particulars. If their hobby is collecting Pokémon cards, we might promise to buy them a few packs if they do well in their exams. We would absolutely not enter into interminable cycles of "debate", and pointlessly consider: Is the hobby of collecting Pokémon cards, on the whole, beneficial to society? Since economically disadvantaged (poor) parents can't afford to buy their children Pokémon cards, is it anti-meritocratic to encourage only some children with Pokémon cards? If for the sake of fairness we wanted to buy every child Pokémon cards, is that economically sound? And so on, and so on, until we inevitably lose interest and, having accomplished nothing whatsoever, abandon the topic (and our unfortunate niece or nephew) entirely.

Going by results, then, we would have completely and utterly failed.

Now, you might find the arguments I made above unsatisfactory, even if you can't quite pinpoint why. But I would wager a guess that it's because they violate the implicit beliefs that educated people hold in our post-Enlightenment society. Namely: 1) Being an educated person, we have a responsibility to nurture wide-ranging interests and knowledge, and at the same time forsake our parochial interests and instead take the interests of the world as our own. Only then can we fulfill our duties as citizens of the world. 2) The story of human progress is the story of increasing abstraction. From scattered tribes we unified into warring kingdoms into nation states. At the same time, manifold scientific observations and principles were also unified into universal theories. That is to say, human progress is equivalent to increasing abstraction, which is equivalent to something we ought to pursue. 3) The ability, or lack of ability, to make abstract arguments is a signal of a person's intelligence and education, and the more abstract their argument, the more intelligent and educated they are.

And like, I don't fully disagree with these ideas. In the first place, I suspect I value them more than most people, which is why I thought enough about them to write an essay on it. And it's obviously good to have wide-ranging interests and knowledge, just as humanity’s ceaseless progress is obviously good. And of course I think abstraction has a lot to do with why humanity has progressed as much as it did. But, ultimately, it was not bookish nerds hiding in the libraries of their family estates that dismantled the superstitious societies of the past. Rather, it was those who wielded knowledge to create new and terrifying possibilities; the scientists, the ministers, the princes, the generals, the entrepreneurs; anyone willing to plunge their hands into society's formative clay. As long as the enemy kingdom had more accurate and longer-range weapons, as long as owing to meritocratic reforms they had a better officer corps - no sovereign could turn their eyes away from practical knowledge. Nor could the ordinary person ignore the radical encheapening of his clothing, food, and household tools, much less the electric poles going up in his neighbourhood, or the railroad tracks cutting across his country.

To accept the world in its full complexity; to try and solve the problems that can be solved; to try and put aside the problems that either cannot be solved or cost more to solve than the solution is worth; to judge every part of every problem to determine which part falls in which category; to always reach our hand out for new tools, so that problems once unsolvable become gradually solvable; to adjust our judgements for the interactions between all these different puzzle pieces - every step takes more effort than the last. But if we truly believe that "knowledge" is the tree that bore us the fruit of our technologically advanced modern society, then no matter how much effort we would need, we would absolutely not accept a demon-haunted world, where nothing we do or think is worth a damn.

On the other hand, if we think of "knowledge" as merely a kind of vainglorious costume, which we wear to signal our suitability to the information-driven modern age… Why bother? As long as we are able to summon cliche rebuttals against cliche arguments, as long as we are able to climb the next step of Escher’s staircase, we will have the praise we crave. And under those constraints we will naturally choose to focus on those big, "important", unsolvable problems; then turn around and say we have no choice but to simplify these complicated problems into incoherent mush.

Psychology today is mired in exactly this kind of sorry state. Obviously, Psych grads are much less respected than, say, Physics grads. But why? Sure, psychology is currently having a replication crisis, but that's not psychology's real problem. As psychology researcher Adam Mastroianni brilliantly pointed out, the problem is that whether or not a study replicates seems to be completely irrelevant to everyone, even to psychology researchers themselves. If studies were your family and friends, and those family and friends were on a plane, and the plane was shot down by Russia anti-air missiles hit by a bird and crashed, wouldn't you care, just a little bit, which of your family and friends were on the plane? Shouldn’t it matter to you whether it was your dearest mother, or the former colleague you haven't met in ten years, who you never really liked in the first place?

We "educated people" are too used to defending the universal worth of an idealised kind of knowledge. Consider the statement: "Even though the Humanities do not train students’ job skills, we should still subsidise them as they train students on the ever increasingly important skill of critical thinking." Even taking for granted that critical thinking should be prioritised over job skills, are the Humanities the only way to train critical thinking? The best way?

Every time some proud know-nothing points out how some study appears to be ridiculous, we "educated people" immediately point out studies which appear to have little immediate use, but in the end transformed the world - As if every study is equal in importance and expected value to Physics' research into the inner workings of atoms.

How convenient! Out of all the infinite possible studies in this complex world of ours, we have somehow already selected the very best!

(I have a strong belief that people who say the education system should more strongly nurture critical thinking have no idea what they're going on about. Suppose we are a doctor considering whether we should give fever medication to a patient. If the patient is otherwise in good health and their fever is relatively low, we should let the fever continue to weaken whatever pathogen they have. On the other hand, if the patient is in a critical condition and a fever will likely push them off the mortal coil, then obviously we should give them fever medication. Whether we should give the medication is entirely dependent on the facts of the patient’s case, and no amount of "critical thinking" will return the correct answer. And, in my personal experience, when I spot issues with the logic of some argument, it's almost always because it subtly doesn't conform to my background knowledge, giving me a bad vibe that I can then pick at. Because logic is fundamentally a process of constructing a set of coherent premises, anyone who wants to cultivate "critical thinking" necessarily has to accumulate more coherent premises. To steal an analogy from the similar "skills vs knowledge" debate: we do not have a choice of "cake" vs "egg", we need the egg to make the cake!)

Through this unthinking, indiscriminate extolling of all knowledge, we naturally forget what knowledge is even for. Though evolution does not favour intelligence, humans still dominate the planet, precisely because intelligence allows us to discriminate; by creating more complex models we are able to choose, with a greater success rate than chance, to ignore certain short-term incentives in favour of longer-term gains. To innovate new, more precise and longer-ranged weapons requires investment. To challenge the nobility and establish a merit-based system requires investment. To lay down railroad tracks across the entire nation requires investment. Are the short-term costs of these investments worth their long-term benefits? If so, which out of the thousand possible implementations is suited to our particular circumstances? Whether we chase innovation or seek stability; whether we bravely attack or prudently retreat; whether we have faith in the wisdom of our elders or put trust in our own experiences - we were born damned to choose.

When I started writing this essay, I intended to blame the education system for stripping people of their judgement, and teaching an over-reliance on pre-approved expert knowledge. After all, when exams determine whether you ascend to (near) the top of society or fall to its very bottom, we have more than a little incentive to memorise and repeat pre-defined "correct" answers. At the same time, a student who demonstrates in their speech and writing an enlightened attitude, as well as their broad interests and background knowledge, will naturally score better and win greater applause from their teachers. But the more I thought about this explanation, the more I realised it couldn't be correct. At least, not fully correct. In the first place, most people don't care about whatever the hell the education system wants them to do! As for "fulfilling our duties as citizens of the world", HAHAHAHAHAHA.

Moreover, over-reliance on conventional knowledge or "common sense" is not limited to the educated. Just imagine a stereotypical taxi driver and put yourself in the backseat as he rants about some group or another while violating every logical fallacy along the way. We just don't care about his bad arguments because, compared to someone who is "educated", our expectations for him approaches zero.

An ice cube is cold not because it has the property of "cold", but because it lacks the property of "heat". The reason we struggle to grapple with the full complexity of the world is not because we for some dumbass reason decided to cover our eyes with blindfolds, but because the task is inherently difficult. The only thing the education system can be blamed for is failing to extricate us from this original sin.

Since I have been having a lot of fun poking at the weaknesses of the education system, I feel a need to defend it in this conclusion. I mentioned earlier that the education system incentivises memorising and repeating certain pre-defined "correct" answers. The implication being, this inculcates a belief in there always being a simple, "correct" answer for whatever problem that exists. But the latter does not necessarily follow from the former.

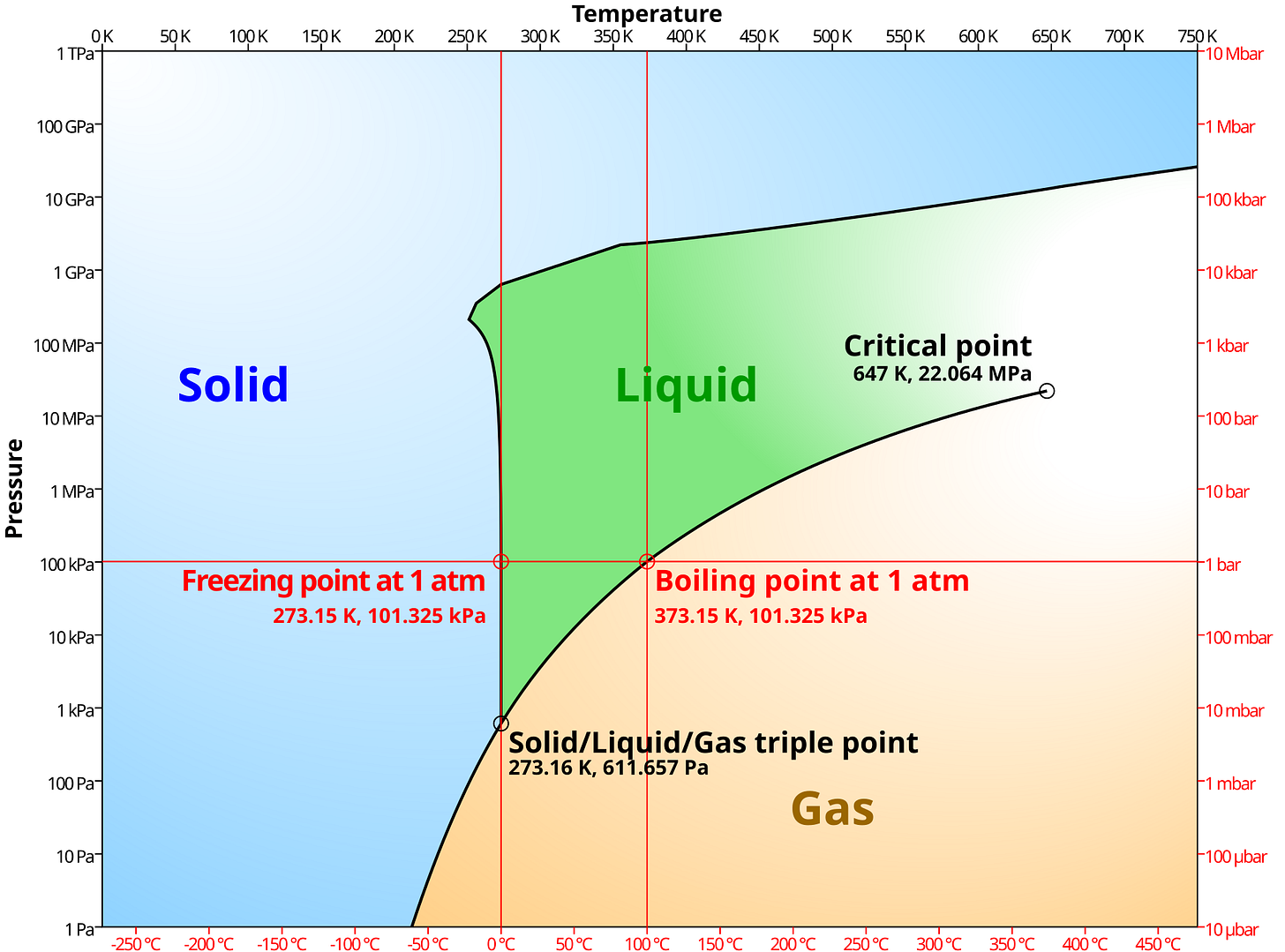

Suppose I asked you suddenly, "What is the boiling point of water?" You might very reasonably say "100 degrees Celsius." But if I reminded you that that was not the correct answer, you might remember that "Water boils at a lower temperature on a mountain", and then pull from the recesses of your memory, "Water's boiling point depends on both temperature AND pressure." In other words, the education system has already taught us at least one lesson on the complexities of the world.

So why have we failed to remember it?