On "Truth"

...and how we find it.

The Rightness of Being Wrong

All “learning” operationally means is that something about the organism’s interaction with the environment caused a change in the information states of the brain, by mechanisms unexplained. […] Attempting to construct a science built around [learning] as a unitary concept is as misguided as attempting to develop a robust science of white things (egg shells, clouds, O-type stars, Pat Boone, human scleras, bones, first generation MacBooks, dandelion sap, lilies…).

John Tooby, What Scientific Idea is Ready for Retirement?

What exactly does it mean to know something, or to learn something? I often come across the idea that ChatGPT should not be used for learning because it sometimes hallucinates, and therefore it’s possible to sometimes learn wrong things from it.

This idea bothers me a lot, because ChatGPT has been extremely helpful for me in learning things. Like, I like watching Physics/Maths/Engineering/etc. videos, and boldly venturing forth into textbooks on topics I’m under-leveled for, but there’s always some pre-requisite knowledge that I either do not have or have returned to sender. And then I’m stuck, because 1) I am by default skeptical of learning anything I don’t fully understand, and 2) it’s always easier to remember a coherent set of facts than a disparate set of facts (e.g. if A and B imply C, then even if you forget C, C tends to re-emerge naturally.)

In theory, I could just “refer to a textbook” to fill in the gaps in my knowledge. But for as long as I have wanted to be a polymath (ever since I read a Horrible Histories book about Leonardo Da Vinci in the school library as a wee child), I have never ever once done that because searching for a particular fact in a particular textbook is a PITA and, in any case, there was no guarantee I would find what I was looking for even if I went through the effort. Whereas ChatGPT just evaporates this friction/search cost, and now I spend my weekends reading up on obscure topics, looking up ChatGPT for step-by-step derivations, and throwing anything that seems important into Anki.

(…Then I spend my weekdays suspending/deleting half of the cards I added because I added too many relatively unimportant cards, but, as we shall later discuss, weighing the relative importance of difference pieces of knowledge is both a necessary and major part of knowledge management.)

So now we have a seeming contradiction: How can ChatGPT be so useful, yet so often so obviously wrong? The pieces of the puzzle snapped into place for me when I read the absolutely profound The Mind in the Wheel series of essays, and in particular this quote by Antoine Lavoisier:

…strictly speaking, we are not obliged to suppose [caloric] to be a real substance; it being sufficient … that it be considered as the repulsive cause, whatever that may be, which separates the particles of matter from each other; so that we are still at liberty to investigate its effects in an abstract and mathematical manner.

The context of the quote is Lavoisier’s proposal of the idea of “caloric”, that is, “small particles of heat” that can slip into the gaps between larger particles of matter, thereby explaining why matter tends to expand when it gets hot.

Of course, two centuries on from the formative chaos of the Enlightenment, we now know that heat is not a particle, but that’s not what’s interesting about the quote. What’s interesting about the quote is that Lavoisier was fully aware that he might have been wrong, and he was fully aware that it didn’t matter. And he knew it didn’t matter because all he needed was something that explained what he already knew, and that he could empirically test.

(I would strongly recommend reading at least the first post of The Mind in the Wheel series. It has that wonderful and frustrating quality of having written down every idea I thought I was brilliant for figuring out, except much better and three months before I had ever even thought of them.)

In other words: If as far as I can tell what ChatGPT is telling me is correct, then it is effectively correct*. Whether it is ultimately correct, is something I am by definition in no position to pass judgements on. It may prove to be incorrect later, by contradicting some new fact (or by contradicting itself), but these corrections are just an unavoidable part of what it means to learn.

Does this back and forth seem unnecessary? Surely, if there already exists a correct answer in a textbook somewhere, it’s absurd to learn the wrong thing first through ChatGPT, then learn the correction? But the apparent absurdity assumes that the correct answer can be easily found. Is it also absurd for a Scottish mathematician to re-derive proofs an Indian mathematician has presumably already discovered centuries ago, rather than embark on a months-long journey to India to find this derivation in an ancient book of proofs?

There’s a trap that I’ve fallen into in the past and I think most people who have tried being serious about learning things fall into, which is that its very hard to determine whether something is true. So if our heuristic is that we should learn something only if we can be absolutely sure that it is true, what we will learn is absolutely nothing. Actually, the problem is even worse than that, because we only become confident that a new fact is true when we know a lot of facts, and that new fact doesn’t contradict any other fact we know. Failure to learn wrong things sometimes means we become stuck in an equilibrium where we don’t know anything and therefore don’t dare to learn anything.

Can we really trust ourselves to learn mostly right things, so that truths will eventually reject falsehoods, as opposed to being sucked into a whirlpool of falsehoods so turbulent that everything seems to contradict everything else and nothing makes sense? I think it’s important here to disambiguate between what we can trust ourselves to do, and what we can trust society to do. It’s obviously possible for a person to become mired in conspiracies, but that does not then imply it’s impossible or even difficult to determine with reasonable accuracy what is true.

There is a “gotcha” argument I’ve come across, which is that if you don’t know a topic well it’s impossible to determine when ChatGPT is hallucinating, but if you already know a topic well you don’t need ChatGPT. I think this argument assumes a non-existent symmetry. It’s almost always much easier to check that an answer is correct than to answer correctly. Just try solving this sudoku. Is it easier or harder to solve it than to check that it follows sudoku rules? Or consider the stereotypical snapback to complaints about a restaurant’s food. You cook it then. But obviously it’s easier to tell when food has been cooked badly than to cook good food. If you have a box that generates Nobel prize-winning ideas 10% of the time, and all you have to do is check whether any particular idea is part of that 10%, then what you have is many Nobel prizes as your heart desires.

I’m not saying there’s no reason to insist on rules like “listen to the experts, only learn what is true”, but the reason is not that it’s more efficient at the individual level. It’s the same reason journals insist on a 5% significance threshold even though its arbitrary and doesn’t really do a good job separating good from bad research. It’s a rule that is plausibly more efficient at the aggregate level, not because it’s impossible to do much better, but because it’s possible to do much worse.

But I am not the entire scientific community. Who cares if I’m slightly wrong in the short term, it it makes me less wrong (heh) in the long term? Absolutely nobody. (Though, to be fair, I don’t think anybody really cares if I’m wrong in the long term either, lul.)

*I had a useful discussion with a commenter on Reddit, on the use of the term “effectively true” instead of “really strong belief” to capture the idea that even someone who has been diligently studying a field for 30 years will still believe to be true things that are “falsehoods I believe, because I cannot push back on it”. After some thought, I think my phrasing is still more correct. The reason for that is that while both terms point to the same state of things, they have different connotations, and therefore imply different reactions to that state. “Effectively true” says “this is the best you could possibly do at this point, and the ‘moral’ thing to do now is to do something else. “Really strong belief” says “the ‘moral’ thing to do is to keep looking.” Since I’m trying to argue against the shibboleth that ‘keep looking’ is unconditionally leads to the truth, it doesn’t make sense for me to use a definition that excludes what I’m trying to include.

Two Definitions of Truth

There is a more fundamental point I want to make, which is that knowledge is not static.

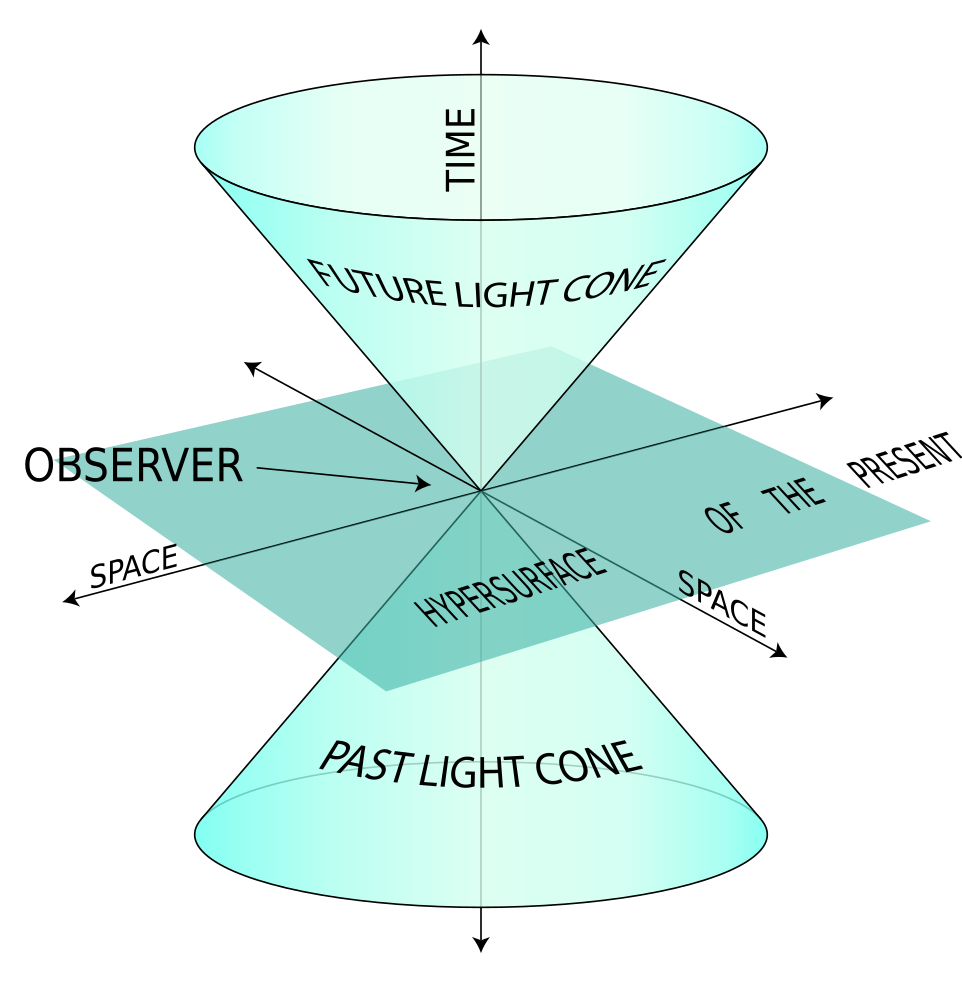

Knowledge is not static because there is no singular “truth”, and there is no singular truth because 1) things are always changing, and 2) information requires time to propagate. Consider this: If I send true information from point A at time t=0, and you receive the information at point B at time t=1 that no longer matches what is happening at point A at time t=1, is the information you receive true or not true?

We feel a sense of paradox, because two definitions of truth have been conflated. The first being that information is true if it corresponds to the process that produced it (which our information packet satisfies), and the second being that information is true if it is always and everywhere true (which our information packet fails to satisfy).

Both definitions are worth discussing. The first definition (the correspondence definition) is more fundamental. It’s why learning works at all. Just by using mental models that correspond to observations, we’re able to “see” space-time bending in our minds, long before we are able to empirically observe it. But this power comes at the cost of complexity: Because we don’t perfectly know the initial state of the world, and because different states of the world can “look the same” within a limited observation window (if it’s a window in space, things could look different outside the window; if it’s a snapshot in time, things could be in the same positions, but at different velocities), we now need to keep track of multiple possible states of the world.

The second definition (the always and everywhere definition), while in some cases applies to things which are inexplicably always literally true (e.g. Newton’s Law, Maxwell’s equations), is in other cases more of heuristic that allows us to control complexity. Granted, it’s a very powerful heuristic, because for some reason our universe is full of systems that converge to stable states, or at least don’t diverge outside of some bounds.

(That our universe seems to like to converge to stable states is a bit hard to formally prove, but I think it’s an intuitive enough claim that I think most people can accept it as is. That said, here’s an anthropic argument I find amusing, if not necessarily convincing: If something continuously diverges relative to a reference process, then it must eventually become too big or too small to remain observable. Therefore, whatever we can still observe must necessarily be the result of a non-divergent process, or at least a process that has only started diverging, or else diverges very slowly relative to the time frame we care about. There’s a great Futurama clip that captures this idea, where an evil AI Amazon expands to envelop the Earth, then the Sun, and then the whole Universe, at which point everything becomes exactly as it was before.)

Our entire system of measurements rely on reference objects that are more stable than the objects we want to measure. Most of the time, when we say something is true, what we really mean is that it is stable. That’s why mirages and speculative investments feel false, but the idea of the United States of America feels real, even though there’s nothing we can physically point to that we can call “the United States of America”.

For a concept that I kept seeing everywhere (“...converges in distribution to a normal distribution” in Statistics, every equilibrium in Physics), it somehow never occurred to me until quite recently how fundamental the idea of convergence was. Without convergence it would be practically impossible to know anything!

Like, what even is “probability”? We assume that the current state we are observing deterministically followed from some previous state according to some set of rules. We don’t know what the rules are, exactly, so we make a model that approximates the observed outcomes.

But what exactly is an “outcome”? Suppose I throw a die in a spaceship, in a submarine, in a dive bar etc. and they all land on the side the shows six black dots facing up but rotated at different angles and lying on different surfaces. Are these three outcomes or just one? If you claim that they’re all the same outcome, and that these differences don’t matter, what justifies the claim?

We define all specific instances of “landing on 6” as equivalent, even though there are many different things about each die roll, because when we place a bet on the outcome of a die, we only bet on the number of dots facing up. So our mental model of the die compresses its entire end state space, throwing away information about an infinite number of “micro-states” to just six possible “macro-states” of a die, because only those are relevant to the future outcome of the bet.

But it also does something else: If I go back to the past, one microsecond before the die lands flat, a larger infinite number of “micro-states” of dice in the air converge onto a smaller infinite number of micro-states of dice on flat surfaces. What if our universe worked by different rules, and every time we threw a die it multiplied into an arbitrary number of new dice? How would we even define probability then? Which is to say, a probabilistic model compresses information by mapping many micro-states to single macro-states, but this compression is only ontologically valid because we are modelling a convergent (or at least non-divergent) process.

(For my own sanity, I’ll be using convergent/non-divergent somewhat loosely from here on, rather than have to pedantically write both every time.)

It always confused me why the Central Limit Theorem worked. Sure, I could work through the derivation, and I could accept each step of the derivation, but I would still not understand why the sample means of arbitrary distributions should necessarily converge towards normal distributions. Until I realised that my bad habit of not reading definitions carefully had doomed me once again, and had I properly read the statement of the theorem, I would have realised that the CLT only applies to distributions with finite mean and variance. In other words, it only applies to distributions that model a convergent process.

Which, of course the sample mean of a convergent process converges!

The requirement of a convergent process has more serious implications than just making the CLT feel more intuitive. Any time we rely on any statistical method that uses the CLT, we are relying on the assumption that the process we’re modelling is convergent. It’s one thing to say “averages are misleading, you could drown in a river that’s on average a metre deep” due to mistakenly aggregating data points from vastly different sub-groups. It’s another to say there isn’t even a meaningful average for any sub-group, because the process we’re modelling is actively diverging. When I think of statistical claims that fail to consider whether the underlying process is changing, and also really stick in my craw, I’m thinking very specifically about statistical claims about intelligence. But I’ll get more into that later, so let’s move on for now.

Modelling knowledge as dynamic also solves a paradox for me: In Statistics (at least in the context of Psychology and Economics, which are slightly more familiar to me), its a big no-no to look at the data, form a hypothesis from the data, then verify that yes indeed our hypothesis matches what we observed.

But this made no sense to me because 1) it implies that to form a valid hypothesis, you need to have never observed any empirical data, and essentially make hypotheses at random, and 2) the process of observing things and coming up with rules that could have generated those observations is exactly how early scientists came up with rules like e.g. KE = 1/2 mv^2, and those rules seem to work perfectly fine.

And I think the solution to this paradox is that knowledge in Physics converges much faster than knowledge either Psychology or Economics. So in Physics we can safely assume anything at the scale we can observe is already stable, whereas in something like Economics we don’t have the same guarantee. Using different data is a soft check that we’re in a semi-stable, somewhat generalisable region of observations.

The Structure of Knowledge

My problem now is that people will see my smoky jalapeño cheddar zucchini fritters, ask for a recipe, then understandably go, “Hey man, I’m not going to bake a loaf of bread just to make a fritter.” Cooking is often described as this process where you just follow instructions […] But a lot of my real, everyday cooking is more like this, […] made in a way that I’ll probably never ever replicate again, because each dish is executed as a response to the context surrounding that meal’s specific circumstances.

Internet Shaquille, The Worst Bread Is The Best Lesson

If we have discovered a fundamental law, which asserts that the force is equal to the mass times the acceleration, and then define the force to be the mass times the acceleration, we have found out nothing.

Richard Feynman, Lecture 12, Characteristics of Force

Knowledge is also dynamic in the sense of: What I know today different from what I know yesterday, in a way that’s more complex than just adding/learning or subtracting/forgetting facts.

A lot of ink has been spilled and social structures decried over students forgetting what they’ve learnt over school holidays or adults forgetting most of what they’ve learnt in school. One argument I find plausible for why its still a net benefit to put everyone through school is that even if individuals forget, society as a whole remembers.

Like, I remember plenty of times I told someone something, forgot it, and then they ended up telling it back to me. In this view, packets of knowledge circulate around like boats on a river. Even if some of them sink, the important thing is that some of them get to where they need to be.

But another view we can take is that of packets of knowledge filling up warehouses long before they are needed, like a huge shipment of widgets for a specific model of car, that not only takes up space that could be used for more immediately useful things, but also rusts into uselessness long before anyone even attempts to put them to use.

(Sidenote: I find the argument that going to colleges for four years somehow necessarily shapes the minds of students in some kind of vague, but beneficial way to be unconvincing. I’m old enough to remember the ‘controversy’ about violent video games, where on one side of the debate I had my personal experience that, no, I did not go about whacking people over the head with a clothing pole after playing Dynasty Warriors; and on the other side of the debate we had on dubious studies about willingness to inflict hot sauce after playing video games.

Which is to say, minds are not that easy to rewire, and if they were, they would not be thereafter impossible to rewire by, like, playing Harvest Moon or something. Intuitively, context mediates what behaviours/mental habits are learnt, and what is learnt is only kept if maintained — actively if the habit is costly, or passively if the habit is triggered frequently enough and costs little enough that it can self-reinforce through repetition. There’s no particular reason to assume that this is likely to happen for all or even a majority of students.)

Knowledge decays. To some extent, this decay is good. The fuller our warehouse is, the harder it will be to find what we want in it. I think this idea and a lot of ideas in this essay are more obvious to me as a software engineer, because software engineering as a field thinks very explicitly about the organisation of knowledge. We cache the results of database reads we expect to use again soon, so we can make cheap cache reads instead of expensive database reads. We put CDNs between the server in the U.S. and the person loading videos in Asia so our horsegirl waifus don’t have to be fetched from halfway around the world.

Knowing that we can organise knowledge to make the use of it 500 times more effective is an awesome power, but with awesome power comes the equally awesome PITA of actually having to organise said knowledge, because now we need to keep track of:

Is this knowledge directly, practically useful?

If it is not directly useful, can it be eventually useful in constructing something that is?

Out of all knowledge that satisfies either the first or second criteria, which should I learn now, based on (non-exhaustively):

Do I have enough pre-requisites that I can make progress?

Which is most immediately useful e.g. learning a new tool for my job vs studying Physics?

Which has the largest long-term payoff e.g. learning a new tool for my job vs Physics?

Which has the most support e.g. teachers who can teach the thing, or at least friends who are learning the same thing?

Which is most “coherent” with other things I’ve learnt recently, since it’s easier to learn/not forget a coherent set of facts? (Annoyingly, this trades off against interest saturation, where you get bored of doing the same or similar things for too long.)

Which is “small enough” that I can actually learn it in the free time that I have? (As opposed to getting extremely confused, running out time, then having to start over from the beginning the next time I try again.)

And the answers to all of these questions are changing dynamically, because learning one set of things makes learning a second things easier, and at the same time it means I’m actively forgetting a third set of things. Add to that, the free time I have is always changing, and what I consider immediately useful also changes every time I get pissed by a Physics lesson or 3Blue1Brown video that I just. don’t. get.

There is also something else that I think anyone who has spent a good amount of time trying to learn difficult things intuitively gets, but I don’t think I’ve ever come across someone explaining it explicitly. There is something very natural about representing knowledge as a kind of directed graph, where some nodes are central, and others kind of secondary. So something like F = ma is more fundamental than, say, something like a = v^2/r for centripetal acceleration, even though both have can be expressed in the form a = something, because you derive the a = v^2/r under the constraint of uniform circular motion, while a = F/m is always true.

And as obvious as that sounds when stated like that, I was very, very confused by equations for the longest time. I knew I was supposed to rearrange the letters in an equation to get a solution, but then when I tried to rearrange the letters I would somehow get a contradiction. And the problem was that maths is fucking bullshit no one ever tells you that the maths that is written down is missing a bunch of stuff you’re just supposed to keep track of in your head. What’s the difference between a function and a transform? Or a function and an equation? Absolutely nothing, except for what you’re mentally mapping the letters to.

If we have a whole bunch of letters interspersed with operators and an equal sign, there are any number of things we could be describing. We could be describing a universal constraint, like F = ma. We could be describing a universal update rule, like a = F/m or the curl of E = -dB/dt. We could be describing a conditional constraint or update rule, like V = IR for for resistors or a = v^2/r for uniform circular motion. We could be describing a guess, like y = βx + ε. Heck, we could just be defining a thing i.e. sticking a label on some useful repeating unit of letters and operators. And because it was never made clear to me that those were all fundamentally different things, as opposed to things the same kind of thing that for unexplained reasons I wasn’t allowed to do the same operations on, I kept getting tangled in contradictions every time I tried to work through a derivation on my own.

I like to think that I was just extremely literal as a child/teenager as opposed to just extremely dumb. So I absolutely love this quote by Judea Pearl, which shows that no, I’m not extremely dumb, confusion caused by the lack of explicit directionality in equations is very common even at the highest levels of some fields:

“Economists essentially never used path diagrams and continue not to use them to this day, relying instead on numerical equations and matrix algebra. A dire consequence of this is that, because algebraic equations are non-direction (that is, x = y is the same as y = x), economists had no notational means to distinguish causal from regression equations.“

Having a sense of what is fundamental and in which direction we’re supposed to go matters. Because the way maths works is that if A and B imply C (and vice versa), you could just as well say B and C imply A, except no, we can’t. Because by trying to derive the general from the specific, we’ve now introduced an assumption that wasn’t supposed to be there and so when we finish re-arranging our letters we will find that somehow 0 = 2.

The only description of knowledge that makes sense to me, is to we start from some base of observations, then somehow or another guess at the rules and entities that could have produced those observations. Now, at this point, neither the empirical observations nor the theoretical rules are necessarily more privileged, since the observations could be mistaken, or the proposed rules could be wrong. But there will be rules that seem more incidental, where changing them would only change one or two specific predictions, and rules that seem more fundamental, where changing them would require changing our entire system of rules. Suppose then we encounter a new claim that contradicts one of our beliefs/rules. We know that either the belief must be wrong or the new claim must be wrong, but which? Should we always reject our original beliefs? Or should we always reject new claims?

I would argue that the only sensible meta-rule is to reject the least fundamental claim. Because even if the universe has conspired to mislead us through coincidence about what’s actually more fundamental, the rules which we perceive to be more fundamental are, in any case, the rules which encode more and a wider variety of observations, and so it’s perfectly sensible to require more contradictory evidence before we reject them.

There also seems to be something like “in-between” rules that don’t map neatly onto any physical object except through convoluted chains of logic, but which allow us to bridge between “clusters” of rules and the observations they encode.

Awareness of the existence of these “bridging rules” solves what used to be a very big problem for me. Because like every overly-stubborn “smart” child, I was very, very insistent on trying to derive everything from first principles, which works out about as well as you would expect. But once we have a map of rules and observations laid out like in the diagram above, it becomes clear that 1) there is no privileged starting position to derive everything else from, since we can reasonably start from any “stable” base, and 2) some parts of the structure are inherently much more stable than others.

Rather than insistently trying to cross the swampy ground between domains by clinging onto a narrow rope of one-off proofs, it’s much more practicable to leapfrog from solid ground to solid ground and from those explore outwards with one foot firmly planted on solid ground. We would spend much less time and effort preventing ourselves from sinking into the ground/forgetting what we’ve learned. And because we would start out “close” to the observations that we care about, what we find in our explorations would also tend to be more directly applicable to them.

(Sidenote: I’m aware that many people have tried to do something like making a knowledge graph in some domain and using that to make automated inference, which just... doesn’t work. I’m not entirely sure what accounts for the difference between what I’m describing and those attempts. But I would guess that I’m using the concept of a knowledge graph in a more general way to decide what next I want to learn, as opposed to trying to derive specific conclusions; as well as having a more dynamic approach where I’m dynamically emphasising/de-emphasising nodes as opposed to trying to pin down a static, “canonical” graph.)

(Side-Sidenote: I’m a bit more ambivalent about whether LLMs are “reasoners” than the skeptics are. And I’m sure someone important has explicitly made the point I’m about to make and I just haven’t come across it, but I think the layers of a neural network are doing something other than just representing ever higher levels of abstraction. If we compare a single layer with very many nodes, to the same number of nodes split across multiple layers, they might “flatten out” to the same linear equation, but a multi-layered model is going to update differently, because if it naively changes one rule to make one data point fit better, it’s going to make more data points fit worse much faster than a single-layered model.)

Complexity, the Bane of Greedy Algorithms

In complexity there is agency, if only you have the wit to recognise it, and the agility and the political will to use it. [...] Southeast Asia is a naturally multi-polar region. It’s not just that the U.S. and China are there, but there is Japan, a U.S. ally but whose interests are not exactly the same. There is India, there is South Korea, there is Australia [...]. So there is a multi-polar environment, which increases maneuver space.

Bilahari Kausikan, Managing U.S.-China Competition: The View from Singapore

I think there’s an even more important reason to be skeptical of ‘polycrisis’: buffer mechanisms. The global economy and political system are full of mechanisms that push back against shocks. Supply-and-demand is a great example — when supply falls, elastic demand cushions the short-term impact on prices [...]. [B]uffer mechanisms often push back against problems in addition to the ones they were designed to push back against [...]. In other words, sometimes instead of a polycrisis we get a polysolution.

Noah Smith, Against “Polycrisis”

Jamie said I think we should get black netting and I said, really? Because we’re trying to see light reflecting off of it and […] I’m like, well, more photons are going to bounce off the white fence than the black fence. And Jamie gave me this look which he delighted in giving occasionally which was this like if you say so […]. I got to this point of like are we actually having this discussion […]? And then this thought occurred to my head, in that second, which was this do I have to solve this problem now, or will the world solve this problem for me later?

Adam Savage, The Thought That Shifted Adam Savage's Relationship With Jamie Forever

I love complexity. And if you can in any way describe yourself as an underdog, you should love complexity too. Because, if it was always obvious what the winning strategy or winning investment was, whichever person or institution starts out with the most authority or most money would always win, right? Yet, by some blessed miracle of nature, that’s not how it goes. And besides just being more fun think about, complex systems have many nice qualities to them.

Complexity rewards the persistent. Because optimal choices emerge “randomly” in complex domains, the only way to find more optimal choices is just to spend more time in the domain (or else to have someone else who has spent the time to pass them on to you). I can’t find the video now, but there was a language-learning Youtube who perfectly described it as: Sometimes you watch an anime and the meaning of a word is so perfectly captured in such an emotionally moving scene that now the word is just permanently engraved in your mind. You’ll never forget it. At the same time, it’s not really possible to go out and look for these moments deliberately.

Complexity gives you more ways to be wrong. How is that a good thing, you ask? It’s a good thing because whatever negative thing you think about yourself or the world, you haven’t actually acquired even 1% of the evidence required to prove it. I mentioned earlier I disliked statistical claims about intelligence. I’ve more or less already made my arguments against them implicitly, but this is such an important topic that I feel I should make my arguments more explicit.

First, intelligence is obviously changeable, and is therefore divergent, and therefore (undergraduate) statistics is entirely the wrong tool for the job (at least at an individual level, which is what should matter the most to you anyway; at a societal level intelligence more difficult to change simply because we can’t control other people directly). Second, to the extent intelligence feels unchangeable, it is almost guaranteed that not enough things have been tried. In this essay alone I’ve probably described about twenty specific confusions I had that got me stuck on learning various things. If as a result of those confusions I had jumped to the conclusion that I was just dumb, instead of just missing something, I would’ve gotten absolutely nowhere.

Here’s another example. It seems entirely plausible to me that someone who plays open-world RPGs would be better at visualising translations and rotations in 3D spaces, and therefore would tend to be better at Linear Algebra. Now if someone looked at this student who not only didn’t seem to study, but also spent all their time playing video games, yet somehow did really well in Linear Algebra, the “obvious” conclusion would be that this student was just really intelligent, when in fact they were just really good at playing video games.

I think a lot of people have the sense that, sure, childhood lead exposure reduces intelligence, but once we control for that, genetics is what really matters. Except that’s just post-hoc rationalisation. We could just as easily imagine someone in the 3000s going, sure, not having your milk supplemented with Neural Growth Factor GHXF-1129 reduces your intelligence, but once we control for that, genetics is what really matters. We can’t just define genetics as the residual not explained by known factors, then turn around and say “genetics” so defined means innate/heritable factors. That’s just a really obtuse way to say we don’t know what is innate/heritable and what is not.

(In general, I think a lot of the discussion I see about intelligence suffers from the rube/blegg problem, where one spoke in our definition of intelligence is effectiveness (some people seem to just do more things, better than other people), and another spoke is natural talent (some people seem to learn things faster than other people). Yet effectiveness can obviously be taught, and even very talented children don’t tend to be very effective. This confusion then leads to something like a single-person motte-and-bailey. I’m imagining here a hypothetical, overly self-critical person, where if you try to teach them ways to be more effective they would say its pointless because they’re a slow learner; but if you point out instances where they learnt something quickly they would say its, sure, they learn trivial things quickly, but they fail to do anything important well.)

Complexity rewards model builders. While I would be very, very hesitant to say that people in general weigh the importance of empirical evidence too heavily (because, uh, some people believe the craziest things), if you’re somehow still reading this, then you, like me probably have a pathological need for things to be certain. Which, if you’re like me, you grew up immersed in an online “discourse” which, if you can’t fork out a double-blinded RCT for your claim, well, then that’s just mere speculation.

As an rule to promote empiricism, it’s not very empirically sound. Simply put, there is too much to know for this to work. It’s like trying to track the position and velocity of every particle instead of tracking aggregates like temperature. It’s like trying to count every real number by going 0, 0.1, -0.1, 1, -1, 0.01, ... . Trying to determine the truth this way is so fundamentally unserious, yet it fits a broader pattern in the current culture of universally prescribing narrow, sometime locally optimal rules while disregarding the systemic outcomes of those rules (recommending everyone to see therapists instead of just talking to friends, demanding more “accountability” and paperwork from governments regardless of effectiveness or cost). But at some (very early) point there just will not be enough evidence, and so if we’re going to get anything done at all, we will need a model.

I slightly regret making this post a bit too technical for the average person, because I think I have a good metaphor to get across the importance of mental models. Suppose we pluck your typical lazy, under-performing, acne-riddled high school student and place them in an internet cafe (this example probably makes more sense in Asia, where internet cafes are more common). We might be able to imagine them playing FFXIV for 16 hours straight and still be full of motivation to play more. Does planning the most optimal build or micro-ing skill activations and player positions not require mental effort? Does playing without eating or resting for 16 hours straight not require focus? So why can this dumb-ass student (cough cough, not me) play games so intensely but not study so intensely?

The difference lies in what the game is doing. Now, you could say, something something, dark patterns, something something, Skinner box, and you would be right, but in a not very interesting way. Because I think we’ve all played some soul-devouring idle or gacha game before that’s designed to separate us from our money, and yet we’re not (I hope) still playing it. Dark patterns aren’t magic voodoo. There’s something else happening, something deeper more generalisable than just flashy lights and level up sounds.

A good game is designed so that you always know what you can do next, as well as what exactly will happen if you do. That is, the difference between playing games and studying lies not in the difficulty of the task but in the player’s mental model of the world. And if it’s extremely clear that I the player messed up by trying to block when they should’ve dodged, and they KNOW that the last item they need to craft their +3 Sword of Infinity is gated behind this STUPID-ASS boss they’ve been trying to beat for 3 F*KING HOURS, then it doesn’t matter how narrow the timing of the dodge is, or how far they have to run from the last checkpoint to the boss, they’ll try again and fail again, and try again, and fail again...

Whereas if someone doesn’t know what to do, what they can even do, or what rewards they’ll get for doing it, it’s no wonder that they don’t feel like doing anything.

To be clear, I’m not saying that because we live in a more chaotic and unpredictable world than the intentionally designed world of video games, it’s therefore justified to suffer from the lack of mental models. What I’m saying is: If we don’t want to be stuck holding our hands out in front of us, falteringly stumbling around in the darkness of the immediate present, only ever being able to react to whatever is directly in front of us, well, we’d better get started with building our own mental models, shouldn’t we?

You might say, that’s a lot of work. To which I say, is it though?

This is another problem with an “evidence-based” approach, though more in a “reinforces a bad premise” way, rather than a “directly derives from” way. So during our first years in school we naively accept whatever we’re taught and then oops, now we’ve learnt about logic and just accepting things as they are isn’t good enough for us anymore. Now, we need proof. And technically, we know we’re supposed to skeptically examine everything, not just new things, but that’s, like, too much work man, so in practice we just skeptically examine new things. And so the foundation upon which we build everything we will ever know... is just whatever we happened to have uncritically accepted until we first came across posts or videos with titles like “How to Avoid Being Wrong”, “23 Logical Fallacies”, and so on.

...Is that approach even close to being theoretically justified?

Since I fancy myself a pragmatist, I prefer to start from what I want. Then what I want controls how much effort I put into figuring out whether a specific thing is true. Otherwise trying to figure out whether something is true or not is just a literal black hole (“How do mirrors reflect light?” “Wait, what is light?” “Wait, why do electrons have discrete energy levels?” “Wait, what is energy?” “Wait, why is energy conserved?” “Wait, why is energy NOT conserved?” etc.) If that’s the case then what does it even mean for model-building to be “too much work”? If model-building is the only way to get what I want, then what even is the alternative? Doing the things I want is too much work, so I’m going to do the things I don’t want?

When most adults say they’re “not smart”, what they really mean is that they’re, if not happy, then at least content, and therefore that they would really much rather you just left them alone, thanks. Because I suspect that if their intelligence was denigrated by someone e.g. an overbearing boss, the response would not be fervent or even resigned agreement.

But if that’s not us, if there’s something we really, really want, there’s still an infinity of things we could try that no one else has ever tried before. And sure, it’s annoying that there’s no answer for us to just follow, and sure, there’s really way too many things (and combinations of things!) to try and most of them will do absolutely nothing. But no one who ever tried putting together a soccer team went like, “Oh no! I could only find one Cristiano Ronaldo-tier player, so I guess I’ll just give up now!” Rather, teams are first filled with the obvious super-stars (which in this metaphor would be things like going to college for an in-demand skill), and then we go down one rung on the ladder of obviousness and fill in more of the team, repeating until we get what we want, or until the cost of getting what we want exceeds our desire to get it.

A third problem with a naive “evidence-based” approach is that there’s no universal law that states we can only learn (or communicate) the truth by argument. Knowing the truth just means our minds are in a state of correspondence with reality. It should be self-evident that argument is not the only way to get into that state. Living in Singapore, I often see arguments by opposition supporters along the lines of “Singaporeans are sheep who just accept whatever the government claims instead of thinking critically”, except the Singaporean government has for the most part been working really well and I would suspect the heuristic of “continue doing what works” has a far stronger correspondence to reality than “follow every argument through, even to absurd conclusions”. When the United States forced Japan to open its ports in 1854, it did not do so by sending an flotilla of lawyers. Yet, somehow, the necessity of the Meiji Reforms was accurately conveyed.

Winning an argument is itself just a heuristic. What we’re actually trying to win is reality. And sure, it takes much longer to show reality who’s smarter. But, like, whether we can out-argue someone who hasn’t spent 90% of their post-adolescent life reading arguing with people on the internet is really besides the point. Maybe at some point in the 80s or 90s it was true that everyone made knowledgeable, good faith arguments, and so it was a good heuristic that the people who made the best arguments deserved the most authority. Except that shifted the meta towards making “good” arguments rather than useful arguments, which DDOS’ed every large-scale communication channel with nonsense, and so the meta shifted again to down-weight arguments alone. At least, that’s what I feel I’ve been subconsciously doing.

Who knows, maybe the pendulum will swing back in favour of reasoned debate again, as a pendulum so often does. But I can’t help but feel much more emotionally stirred by a call to action like in this Palladium essay:

“The only thing that matters in ‘culture’ is the ancient formula of ‘undying fame among mortals’ for great deeds of note. The great work is Achilles’ rage on the Trojan plain, Homer’s vivid account of it, the David of Michelangelo, the conquest of Mexico by Cortez, the religious inspiration of Jean d’Arc, the Principia of Newton, the steam engine of Watt, or the rocket expedition to the moon by Wernher von Braun. [...] [T]he best propaganda is the propaganda of the deed.“

...Than by yet another argument on the internet. I suppose that’s my cue to stop indulging in writing blog posts and go back to studying actually useful things.

See you in another few months!

(Well, I hope to write book reviews and such more frequently, but it doesn’t hurt to set expectations low.)

Addendum 1: Non-Linearity in Everything

A question we could ask is why physical systems seem to converge so often (other than the unsatisfactory anthropic argument). To answer this question, I’m going to do that irritating thing where I define something that’s poorly defined, in terms of another thing that’s poorly defined. I think a huge part of why systems converge is because of diminishing returns. Diminishing returns is one of the things you learn about in a specific context, like, “20% of the work gets 80% of the results because of diminishing returns, so you shouldn’t waste time and effort trying to get things perfect.” And you don’t really think about it much outside of that context.

But it’s so much more than that.

When I first read about how poorer families tended to be more generous with helping their family/neighbours, so that when they needed help they would be able to get it, I was very confused. If you’re in that situation, why not just skip helping others that one time, and save enough so that you wouldn’t need help in the future either? Why go to all that hassle just to shuffle the same savings around? It was only later that I realised, oh, it’s because costs are not linear. If you need salt now you could walk over to my house and borrow it instead of driving all the way to the store (at least until your regular grocery day, at which time the marginal time cost of buying salt is zero), and vice versa.

Pretty much every form of social cooperation is a way to unkink non-linear utility or cost functions. Division of labour? Those ten thousand nails I can make in a month by specialising in nail-making aren’t going to do me any good if I’m only making them for myself. Alone, the non-linear increase in my efficiency at producing nails as I spend more time producing them is more than matched the non-linear decrease in my utility (I would starve to death.)

So how exactly does diminishing returns lead to convergence? We could observe that diminishing returns goes up sharply and then has a flat bit at the end, and convergence similarly goes up sharply and has a flat bit at the end, and surely those two observations must be related. But we can do a bit better than that.

Suppose Alice and Bob are both making dongles at a dongle factory, and Alice is a lot better than Bob at making dongles. But suppose you needed keychains to make dongles and both Alice or Bob can make many more dongles than there are keychains to make them with. In the end, both Alice and Bob will make exactly the same number of dongles, Alice will just get there slightly faster than Bob. And maybe it’s obvious that everyone stalls at the frontier of human knowledge. But is it equally obvious that even if Alice has a number of different actions she could do with different potential payoffs, that to a certain extent it doesn’t really matter which action is the most optimal?

If it’s kind of ambiguous whether option A or option B has bigger payoffs, and their payoffs are independent, it’s more optimal to just pick one at random than waste time and effort trying to resolve their actual payoffs. Whichever one we pick to start with, diminishing returns are going to set in, at which point we pick the other. We’ll always end up picking the same set of options over a long enough horizon.

Brilliant read! I operate this way too. I resonated deeply with the resonance with Leonardo Da Vinci. I had a similar cognitive mirroring moment when I was around 13 - 14 after playing assassin’s creed 2 and seeing his mannerisms fleshed out. I don’t idolise or put him on a pedestal. Just a simple cognitive resonance moment.